Cerro Fitz Roy (ca. 3405 m).

General Introduction

Long before the ascent of any these impressive peaks was envisioned and the western explorers discovered this land, the king of this land was the wind, who shared its kingdom with the original inhabitants of this land, the Tehuelches. They referred to this mountain as “Chaltel” or “Chaltén” meaning smoking mountain, a name no doubt inspired by the clouds that so often trail from the summit. Unfortunately the western newcomers had their heads too full of heroes to celebrate and appreciate the poetry of the original Tehuelche name.

It was Francisco Pascasio “Perito” Moreno that renamed the peak after Robert Fitz Roy, an English astronomer and sailor (1805-1865), who was partly responsible for the first accurate mapping of the intricate watersheds and shorelines of Patagonia and Tierra del Fuego. On his second trip to Patagonia in 1834, together with Charles Darwin, Fitz Roy set out to explore the Río Santa Cruz in hopes of reaching the Andes, but after sailing 140 miles up river they were forced to turn around, resigning themselves to a very distant sight of the snow covered mountains. (1)

Of the mountain he later christened as Cerro Fitz Roy Moreno writes: “Los Tehuelches me han mencionado varias veces y con terror supersticioso, esta ‘montaña humenate’. Es el ‘Chalten’ que vomita humo y cenizas y que hace temblar la tierra...” He later on explains his reasons for renaming the peak “Cerro Fitz Roy”: “...como el nombre de ‘Chalten’ que le dan los indios lo aplican ellos también a otras montañas, me permito llamarle ‘Fitz Roy’, como una muestra de gratitud que los argentinos debemos a la memoria del sabio y enérgico almirante inglés...” The reasoning seems in accordance to the principles of the early explores, who felt they were discovering a land that had in fact been inhabited for almost 12.000 years. (2)

The clouds that so often trail the summit tricked everyone, from the Tehuelches to Moreno, into thinking the peak was a volcano. It was not until 1899 that German naturalist Rodolfo Hauthal visited the area and clearly established that the peak was in fact granite.

This ravishing peak epitomizes the beauty of Patagonia; Carlos Comesaña, responsible for the second ascent of the peak wrote: “As if the Pampa, tired of meekness, were kicking up its heels to shake off its century old pace, the fantastic pyramid of Fitz Roy rears up and pierces the sky under glimmering sun or fleecy storm clouds. This ideal of all mountains casts a spell on the climber and is worthy of his greatest efforts.”

From a climbing perspective this stunning peak is best described in the words of American Doug Tompkins, who after a successful ascent in 1968 commented “Fitz Roy was the peak to climb, the terrible Cerro Torre one to have climbed”. This short description of the very diverse character of the mountains in this area still holds true today. Fitz Roy provides some of the most enjoyable and high quality climbing to be found anywhere in the mountains. Its steep golden walls offer clean and mostly ice-free rock, perfect for free climbing, without the added difficulties of the snow mushrooms that cap the Cerro Torre group.

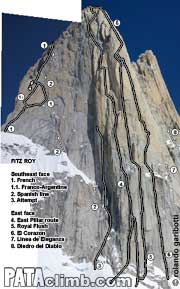

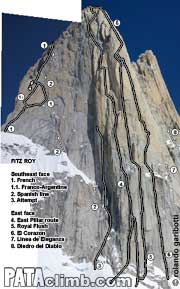

Each of Fitz Roy’s many flanks is particular in a different way; its east face is a big-wall like feature, while it’s north and west faces offer excellent alpine free climbing opportunities and its southeastern side, being it’s shortest, is it’s most popular. The best rock Fitz Roy has to offer is in it’s east and north face, particularly in it’s north pillar.

About 90% of the ascents of this peak have been accomplished by either of its two “normal” routes, the Franco-Argentine and the Californian. Only recently has there been an increased interest in the more obscure, longer and more difficult lines, many of which are still unrepeated. The future holds a vast repertoire of adventures, with countless unclimbed lines and alpine style ascents to be enjoyed.

Climbing history

The first serious attempt to climb the mountain was by three distinguished Italian mountain guides, Ettore Castiglioni, Giovanni “Titta” Gilberti and Leo Dubosc. They were part of an expedition led by Count Aldo Bonacossa. In early 1937 they reached the saddle just south of La Silla, since then referred as “La Brecha de los Italianos”. They had intended to attempt the southwest buttress, the line that much later become the “Californian” route. It was there where they had thought they would find lesser technical difficulties, but they were unable to continue past “La Brecha” because they did not have crampons, having left them somewhere in the couloir leading up top it. (3)

After an early visit to get to know the area in 1947, Argentine resident of Austrian origin Hans Zechner made two serious attempts to climb Fitz Roy, in 1948 and 1949, by the southwest and west faces. Aware of Bonacossa’s team failure on the south face, he decided to try via the opposite side, in hopes of finding a more reasonable route to the summit. It was Zechner who first envisioned the possibility of climbing what would later become the “Supercanaleta”.

In 1948 Zechner attempted the SW face (heading up the Poincenot couloir) and the west face (up “Hombre sentado” from the Torre valley) with Mario Bertone and Nestor Gianolini but they were forced to retreat by falling debris and later on due to lack of bivouac equipment. (4)

In 1949 Zechner returned with Rodolfo Dangl, Roberto Matzi and Agustine “Guzzi” Lantschner. Although they all lived in Argentina they all had been born in the Alps and were well versed in the art of climbing. Unfortunately the first impression marked the rest of the expedition: “...fantastic, grandiose, but much more difficult than we had imagined…”. They made three different attempts from the southwest and west face, reaching the top of the Hombre Sentado ridge twice. In hopes of getting a better look at the possibilty of climbing what would later become known as the “Supercanaleta” they made the first ascent of Cerro Pollone. As the writer Saint Loup pointed out, “this last expedition from Zechner departed with a great handicap, they intended to make a film. However, alpinism does not allow contradictory objectives, and therefore they returned home with a great film.” Saint Loup copntinues, “...Zechner est venu par amour, et revenu avec persévérance, persuadé que cette escalade justifiait les plus grandes sacrifices.” (5)

In the year 1950 the salesian priest Alberto Maria De Agostini, with the guide G. Gambaro made an attempt to climb Fitz Roy. Apparently they were forced to give up the idea due to bad weather. “It is unclear if De Agostini, an experienced explorer, had underestimated the difficulties of the mountain, or if he had overestimated the abilities of his guide, who was not known in the Italian mountaineering circles.” (6)

From this point on, since the first ascent took place in 1952 the climbing history of this peak is found under each and every route page (see links in the route list to the right, happy reading…).

Bibliography.

1- Darwin C. -1845- The Voyage of the Beagle round the World, London, chapter 9.

2- Moreno F. -1879- Viaje a la Patagonia Austral, 1876 a 1878, Bs.As.

3- CAI-Rivista Mensile 1938/10-11 p. 466-475; CAI- Rivista Mensile 1946/3-4 p. 65-77; CAI-Alpinisti Italiani nell Mondo 1953 p.289-291; CAI-Alpinisti Italiani nell Mondo 1972/2 p.818-821; Mario Fantin (1967) Italiani Sulle Montagne dell Mondo, Capelli, CISDAE, Bologna, p. 268-269; Bonacossa A. -1980- Una vita per la montagna, Tamari, Bologna.

4- La Prensa newspaper, Buenos Aires 19/3/1948 p. 8 -2 columns w/photos; Anales de la Sociedad Científica Argentina, Septiembre 1948 Tomo 146 p.163-178; Anuario CAB 1949, p.5-14.

5- Anuario CAB 1950 p. 14-26; Saint Loup (1949) Monts Pacifique, Arthaud, Paris.

6- CAI-Rivista Mensile 1950 p.257; Mario Fantin (1967) Italiani Sulle Montagne dell Mondo, Capelli, CISDAE, Bologna, p. 270.

|

Photos (click to enlarge)

Fitz Roy - north and west face

Fitz Roy - south face

Fitz Roy - east face |